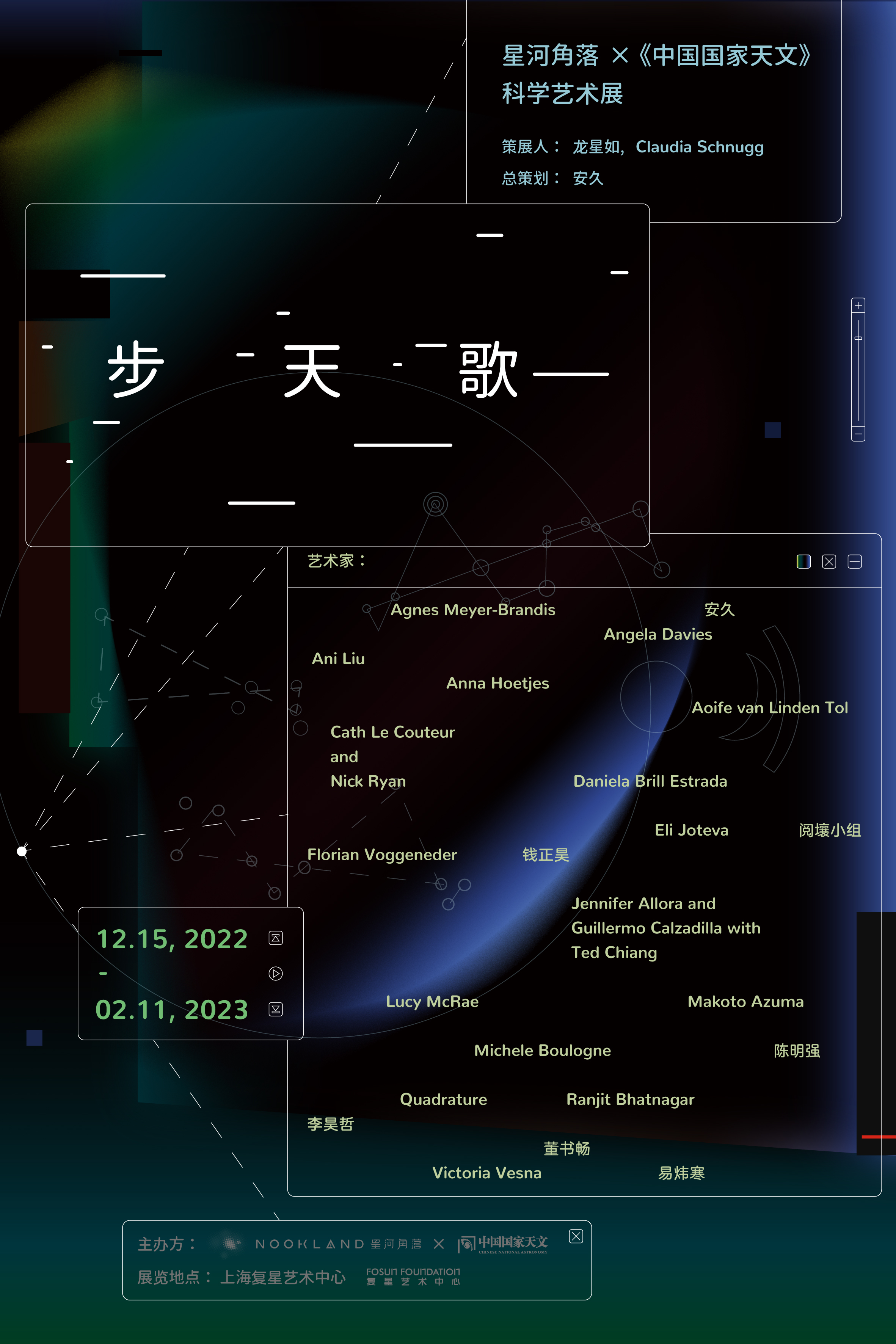

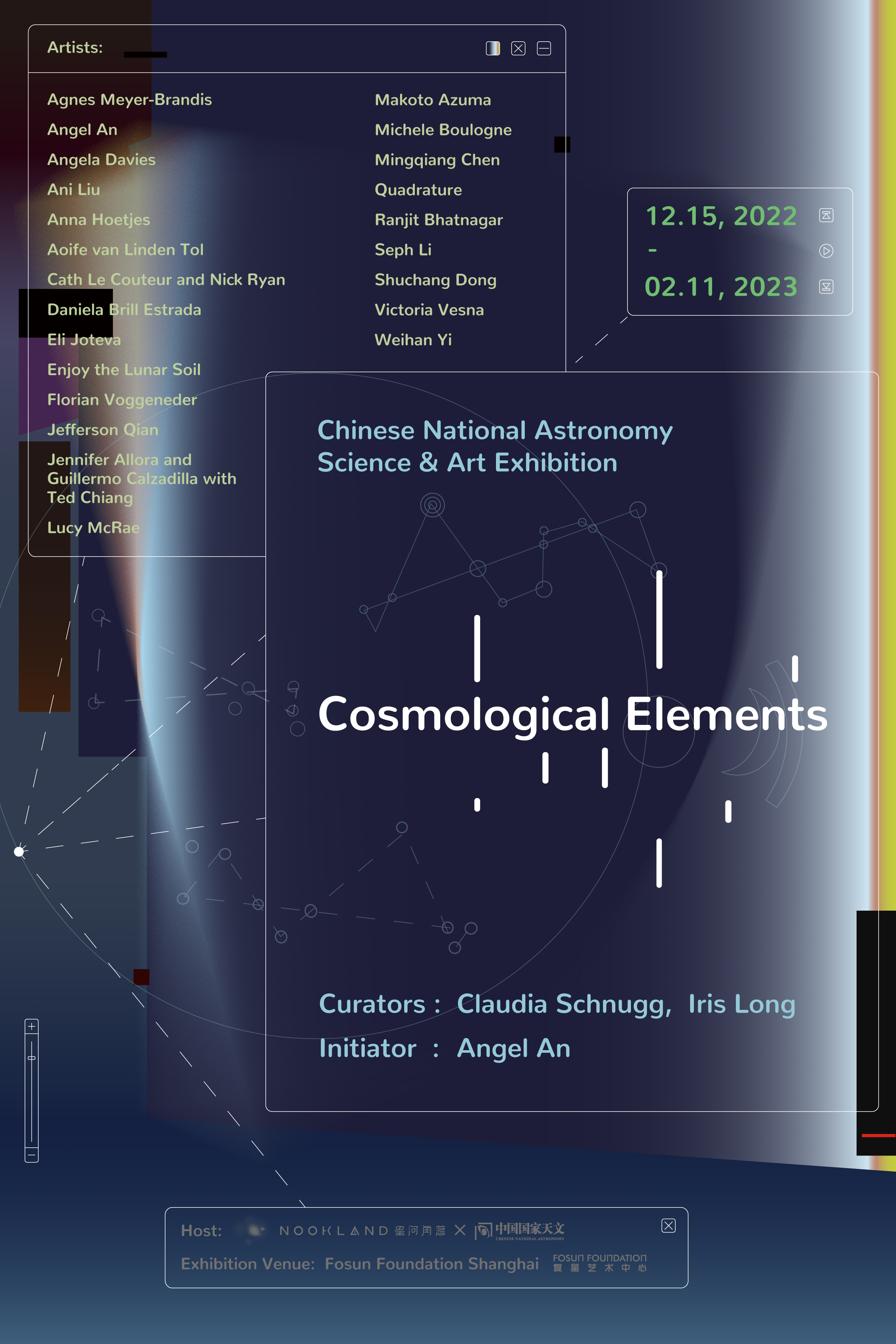

Cosmological Elements 步天歌

15 DEC 2022 - 11 FEB 2023

![]()

![]()

策展人 CURATORS

Claudia Schnugg & 龙星如 Iris LONG

艺术家 ARTISTS

Agnes Meyer-Brandis/Ani Liu/Angela Davies/Anna Hoetjes/安久 Angel A/Aoife van Linden Tol/Cath Le Couteur and Nick Ryan/陈明强 Mingqiang Chen/Daniela Brill Estrada/董书畅 Shuchang Dong/Eli Joteva/Florian Voggenede/Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla with Ted Chiang/李昊哲 Seph Li/Lucy McRae/東信&椎木俊介/Michele Boulogn/钱正昊 Jefferson Qian/Quadrature/Ranjit Bhatnagar/Victoria Vesna/易炜寒 Weihan Y/阅壤小组 Enjoy the Lunar Soil

展览网站 EXHIBITION SITE

www.cosmoelements.art

策展人 CURATORS

Claudia Schnugg & 龙星如 Iris LONG

艺术家 ARTISTS

Agnes Meyer-Brandis/Ani Liu/Angela Davies/Anna Hoetjes/安久 Angel A/Aoife van Linden Tol/Cath Le Couteur and Nick Ryan/陈明强 Mingqiang Chen/Daniela Brill Estrada/董书畅 Shuchang Dong/Eli Joteva/Florian Voggenede/Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla with Ted Chiang/李昊哲 Seph Li/Lucy McRae/東信&椎木俊介/Michele Boulogn/钱正昊 Jefferson Qian/Quadrature/Ranjit Bhatnagar/Victoria Vesna/易炜寒 Weihan Y/阅壤小组 Enjoy the Lunar Soil

展览网站 EXHIBITION SITE

www.cosmoelements.art

步量天地之间,我们与星辰遥相呼应。隋唐以来,以多个版本传世的“步天歌”,在观象台口传却不在民间流转,随着时间推移,“此本只传灵台,不传人间,术家秘之”的步天歌口诀从观象台进入民间,正如“宇宙”也从研究的高阁,成为许多艺术家、摄影师、作家、天文爱好者可以参与、体会和讲述的领域。展览不但‘揭开’了中国古代天文学史的‘秘密档案’,亦试图开启一段共赴宇宙终极浪漫的暗夜之旅 ,让观者探索宇宙和反观自身命运。

从宇宙大爆炸开始,宇宙中的元素、尘埃经过了无数次地分离、又重聚。终于,在无尽星河的漫长等待中,人类出现在了地球这颗漂浮于深空的行星上。人类只有一片天空,地表之上在历史中曾经出现的观星者及他们所处的文明,为这片相同的广袤寰宇提供了各式各样的制图学。从古时的星图,到太空望远镜离开地表拍摄的深空图像,再到不在人眼可见波段的宇宙微波背景辐射(CMB),这些对宇宙的制图也揭示了一种将天空作为大地或海洋的可能,星球可能是板块之上的大地,星际空间可能是海洋尽处的海洋。第一张星图也标志着“天空”从几十亿光年的虚空,转换为可被凝视、追踪、描摹的对象的瞬间,或者说一种天人关系的思维转变。 尽管我们不能在星海中直接航行,但我们都同在一艘名为“地球号”的宇宙飞船上,它承载过几十亿的“乘客”,让我们在宇宙中每秒转动约465米,又随着太阳系以每秒约 20km 的速度向织女星迈进。

展览的中文名“步天歌”意在暗示这种由地球所携带的无意识航行,亦可成为观星者的有意识行动——暗夜在遮蔽视线的同时,也揭示了一整个宇宙的存在。“步天歌”采用三垣、二十八宿将全天星空分为三十一大区,以此观测星空运行规律、测定岁时季节等。被《通志·天文略》称誉为“句中有图,言下见象,或丰或约,无馀无失”。“步天”是一种人身坐标和宇宙坐标之间的动态关系,也是展览重要的概念起点——不论我们对宇宙的认知经历过多少观测与探测技术的革命,我们自身仍然是极为重要的媒介。肉眼尺度上的天河,观天设备尺度上的星体和科学实验设备所追踪的亚原子粒子、暗物质或暗能量,它们并不仅仅是对“客观真实”的描述,也在提示我们与宇宙之间深切而隐秘的关联。哲学家和物理学家凯伦·巴拉德(Karen Barad)谈论了当前的研究如何“与宇宙半路相遇”,社会科学家本特利·B·艾伦(Bentley B. Allan)则试图了解在主流叙事中的宇宙学元素如何转化为社会生活中的目标、愿景和讨论。

从步天歌的隐喻出发,展览进而从“隐藏的维度”、“宇宙生态”和“漂流的文明”三个角度,展开对宇宙空间和个体生命之间关系的思辨。我们试图探索人类对太空的欣赏和敬畏从何而来,是什么推动了关于深空的视觉想象和科学研究,科学发现如何在带来新的宇宙图景的同时,将我们带回人类与构成宇宙的那些最微小元素之间——或者说,我们与星星之间的关系?

“隐藏的维度”试图追溯卡尔·萨根意义下的“恒星物质”(starsstuff)或“星际尘埃”(stardust)的历史(我们DNA中的氮,我们牙齿中的钙,我们血液中的铁,我们苹果派中的碳都是在坍缩恒星的内部制造的)。维多利亚·韦斯那(Victoria Vesna)通过降落在七大洲的陨石,展开一段关于星际尘埃的冥想。丹妮拉·布里尔·埃斯特拉达(Daniela Brill Estrada)在从空中垂降的瓶子中,标注了构成我们的元素的诞生地,和在宇宙中可以找到它的地方。安吉拉·戴维斯(Angela Davies)的作品则进一步启发我们讨论那些支撑生命的基础元素。伊莱·约特瓦(Eli Joteva)和奥伊夫·凡·林登·托尔(Aoife van Linden Tol)分别从可见光谱与不可见光谱的角度,提示我们对宇宙的几乎所有了解,都是在从无线电到伽玛的整个电磁波谱的波长内发现的。安娜·浩特杰斯(Anna Hoetjes)的作品《晨星》则描述了我们收集外星数据的工作与人类对地球的看法之间的平衡。这些作品共同提示着我们和宇宙如何在“隐藏的维度”上深深关联。安久,李昊哲,钱正昊则在《天体乐章》中邀请人通过行走交织出星体的位置关系、明暗变化和化学构成。安久使用氢原子的红色发射线和氧原子的蓝、绿发射线的窄波段图像数据,展示了距离我们约700光年的地方,一颗类似于太阳的恒星正在消逝的场景。这个行星状的发射星云揭示了我们的太阳也许会拥有着相似的未来——也使得“宇宙生态”成为一个更为迫切的议题。

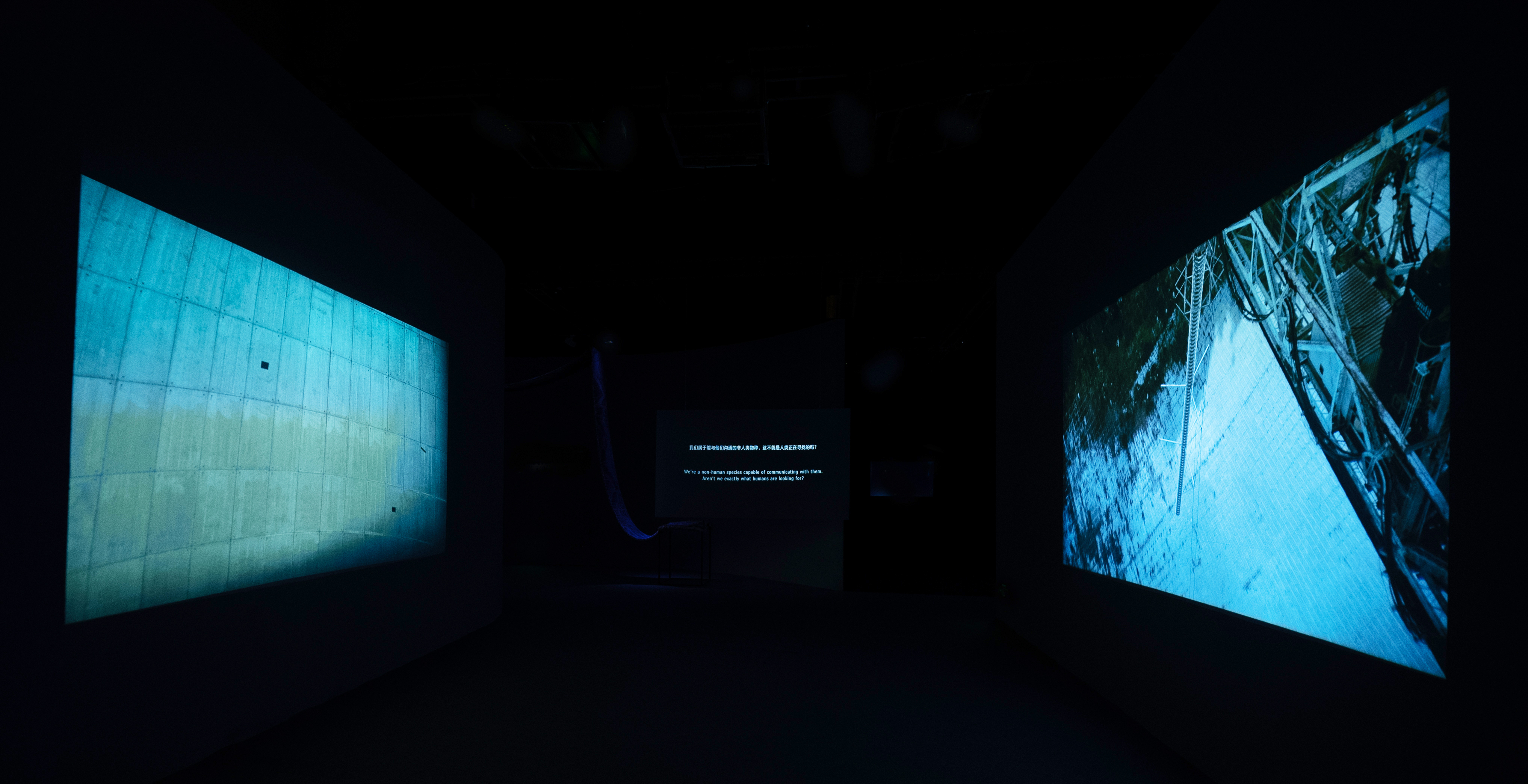

“宇宙生态”在宇宙而非地球的层面想象一个生态环境——当空间的边界拓展到深空场的尽头,人类与其他物种如何在星际层面共存和交流?东信与椎木俊介通过一颗从美国内华达州的黑岩沙漠发射到平流层的气球,让一朵花 “踏入”地球以外的未知领域。这种离开地球表面的向往,意图以天为海或以天为陆的旅行,也使得我们需要从深空的视角理解周遭的一切。Michèle Boulogne,Cath Le Couteur,Nick Ryan和Quadrature等人的作品探讨了小行星采矿的未来、轨道卫星和太空垃圾的秘密世界——用本杰明·布拉顿(Benjamin Bratton)的描述来说,如果“蓝色大理石”是一部电影而非照片,我们会看到最初的火山、风暴和原始海洋如何加速成为一个被卫星、金属和光纤制成的电缆包裹的蓝色计算机。兰吉特·巴特纳加尔(Ranjit Bhatnagar)将“金唱盘”解读成一张空中的挂毯,詹尼弗·阿洛拉与吉列尔莫·卡尔萨迪利亚(Jenniver Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla)与科幻作家特德·姜(Ted Chiang)合作的《大寂静》则通过一则寓言,讲述了阿雷西博天文台附近居住的濒危波多黎各鹦鹉如何旁观人类寻找地外生命的过程——而在这个故事里,“其他的智慧生命”,比如这些掌握了宇宙“声音”(振动)密码的鹦鹉,其实就在我们身边。

“漂流的文明”则将镜头指向那些对人类在太空中长期生存的思考,我们能否适应不同星球上的环境,能否在除地球以外的其他地方建立新的家园? 这一单元的许多作品展开更为科幻的视觉场景,《天空之眼》拼贴了来自荷兰电影博物馆和欧洲航天局的收藏品的内容,并想象探索宇宙的不是穿透力强的火箭,而是缓慢漂浮的气球。《孤独研究所》虚构了一个研究和训练场所,主人公在消声室中研究关于寂静的心理声学,并在微重力训练器中调节身体,以适应可能的太空生活。《月鹅模拟:月球迁徙鸟类设施(MGA)》则根据弗朗西斯·戈德温(Francis Godwin)的《月中人》,想象了白鹅如何迁徙至月球的故事。随着作品从不同的角度串联起人类关于宇宙的感知、记忆、梦想、任务和愿景,弗洛里安·沃格内尔(Florian Voggeneder)同样将虚构的方法与太空旅行的科学愿望联系在一起。Quadrature的《石头》和安妮·刘(Ani Liu)的《地球记忆的嗅觉时间胶囊》则将这种想象推向了极致:当我们离开地球时,我们会留下什么让别人找到我们?在一段单程的太空旅行中,我们如何铭刻关于地球的记忆?

从浑天说、手绘星图到现代的科学技术与宇宙观,我们不断地扑向这片头顶的熠熠星空,就像是镌刻在人类基因里的本能,千百年来没有什么能像星空一样,承载着人类无尽的想象与希望。而我们与宇宙的诸种关联将会由我们自身去探索、去发现。

In pacing out heaven and earth, we commune with the stars. Since the Sui and Tang dynasties, many versions of “Star-Pacing Songs” (butian ge) have come down to us, circulated in observatories without spreading among ordinary people. “This volume should only be disseminated in the observatory and not among the people. It is a secret of specialized practitioners.” With the passage of time, those once-secret instructions moved from the observatory into everyday life. The universe was no longer the sole province of researchers, becoming an area of engagement, experience, and discussion for artists, photographers, authors, and amateur astronomers. The exhibition reveals these confidential archives from ancient Chinese astronomy, but it also takes viewers on a romantic night-time journey to the end of the cosmos, helping them to explore the universe and reflect on their place in it.

Since the Big Bang, elements and dust in the universe have undergone countless separations and combinations. After an endless wait in the vast Milky Way, humanity appeared on Earth, a planet floating in deep space. Humanity only has one piece of sky, and the stargazers who have appeared on Earth throughout history and the civilizations in which they lived have created many forms of cartography for the same vast world. From antique star charts to deep space photographs taken by space telescopes above the surface of the earth and cosmic microwave background (CMB) that is not in the band visible to humans, these charts of the universe also reveal the possibilities that the sky could offer for the earth or ocean. Celestial bodies could offer insight into the land on tectonic plates, and interplanetary space could connect to the water at the depths of the ocean. The first star charts also marked a moment of transition—space shifted from a void several billion light years away into something that could be seen, tracked, and depicted. It also signaled a shift in the relationship between humans and the heavens. Although we cannot fly directly into the starry sky, we are all on a cosmic ship called “Earth” carrying several billion passengers; it rotates at a velocity of 465 m/s and moves toward Vega at 20 km/s with the rest of the solar system.

The Chinese name for the show suggests the unconscious flight of the Earth and the conscious actions of stargazers. Even as the dead of night obscures sightlines, it reveals the presence of the entire cosmos. “Star-Pacing Songs” divide the entire sky into thirty-one large areas: the Three Enclosures (yuan) and the Twenty-Eight Mansions (xiu). The ancient Chinese used this system to make observations about the seasons and the laws of movement in the night sky. Comprehensive Records: Monograph on Astronomy (Tongzhi · Tianwenlüe) praises these songs: “There are images in the words and there are appearances beneath the speech, whether ample or restrained, without excess or loss.” Star-pacing is a dynamic relationship between human and cosmic coordinates, but it is also an important conceptual starting point for this exhibition—no matter how many times our understanding of the universe has been changed by observational technologies, we are still extremely important mediums. The naked eye viewing the Milky Way, the astronomical equipment observing the planets, and the devices in a science lab tracing subatomic particles, dark matter, and dark energy all describe “objective reality,” but they also suggest our profound and mysterious connection with the cosmos. Philosopher and physicist Karen Barad discusses how current research meets the universe halfway, while social scientist Bentley B. Allan attempts to understand how cosmological elements in mainstream narratives become objectives, aspirations, and discussions in social life.

Beginning with the metaphor of the “Star-Pacing Songs,” the exhibition represents the relationship between cosmic space and human life from three perspectives: “Hidden Dimension,” “Cosmic Ecology,” and “Floating Civilizations.” We attempt to probe the source of humanity’s appreciation and reverence for space and the drivers behind the visual imagination of and scientific research into deep space. How does scientific exploration inspire new visions of the cosmos, and bring us back to humanity and the smallest elements that make up the universe or, in other words, our relationship to the stars?

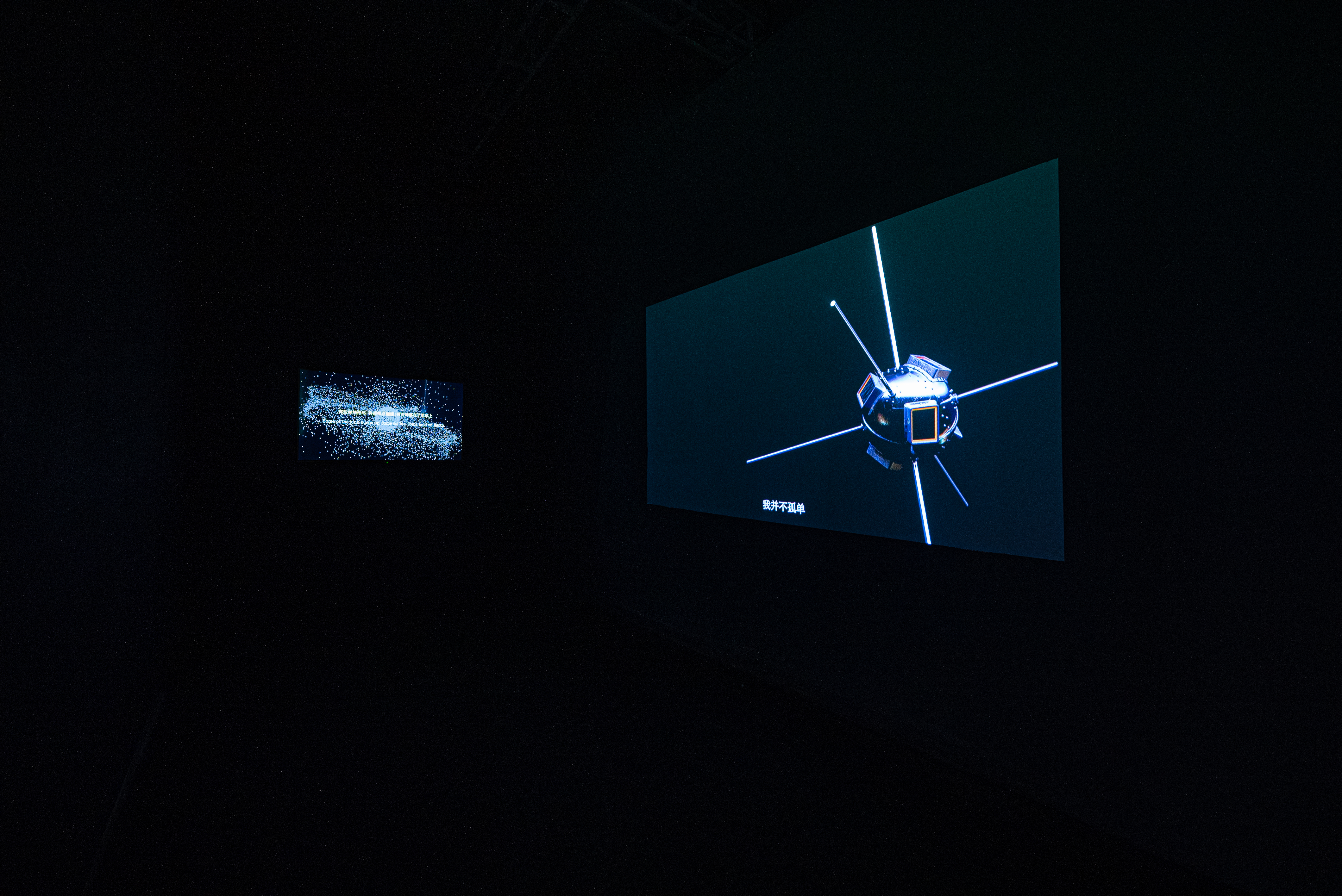

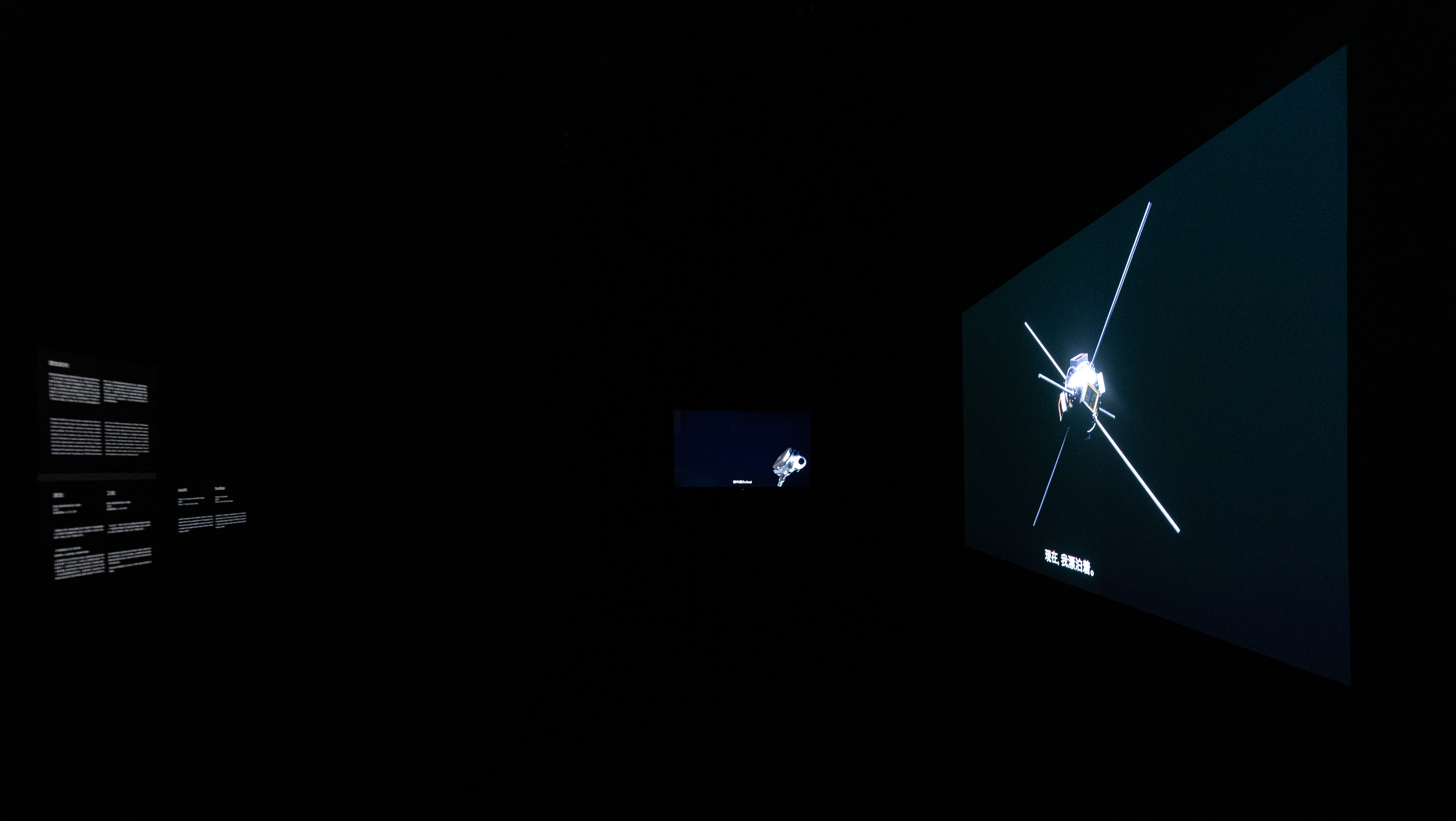

“Hidden Dimensions” attempts to trace the history of stardust or what Carl Sagan called “star-stuff”—"the nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars.” Through meteorites that have landed on all seven continents, Victoria Vesna meditates on stardust, and with bottles suspended in the air, Daniela Brill Estrada marks the birth of the elements that comprise us and traces how they found their place in the cosmos. Angela Davies’ work takes this further pointing to the elements that support life. From the visible and invisible light spectra respectively, Eli Joteva and Aoife van Linden Tol remind us that almost everything we know about the cosmos has been discovered by detecting wavelengths from the electromagnetic spectrum, spanning radio to gamma rays. Anna Hoetjes’ work Morning Star reminds us of the fragile balance of the work that can be done collecting data and the human perspective on Earth that determines the viewpoint. These works of art remind us of the hidden dimensions of our deep connections to the universe. In The Galaxy Orchestra, Angel An, Seph Li, and Qian Zhenghao invite visitors, as they walk, to intermingle the positions, changes in exposure, and chemical compositions of celestial bodies. Angel An uses the narrow-band imaging data from the red emission spectrum of hydrogen atoms and the blue and green emission spectra of oxygen atoms to show that a star like the sun is dying in a place about 700 light-years away from us. This planetary emission nebula shows that our sun may have a similar future—an issue that becomes more pressing in “Cosmic Ecology.”

“Cosmic Ecology” envisions an ecosystem on the cosmic—not earthly—level. When the boundaries of space expand to the end of the deep space field, how will humans and other species coexist and communicate on an interstellar plane? In a balloon launched from the Black Rock Desert in Nevada into the stratosphere, Makoto Azuma and Shiinoki Shunsuke helped a flower “step into” the unknown territory beyond Earth. This desire to leave Earth’s surface, which takes the ocean or land as a surrogate for the sky, means that we need to understand everything around us from the perspective of deep space. The work of Michèle Boulogne, Cath Le Couteur, Nick Ryan, and Quadrature explore the future of asteroid mining, orbiting satellites, and the secret world of space junk. As Benjamin Bratton put it, if The Blue Marble were a film and not a photograph, we would be able to see how quickly the first volcanos, storms, and primitive oceans became a blue computer enveloped in electronic cables comprised of satellites, metal, and fiberoptics. Ranjit Bhatnagar interprets the golden record as a tapestry in the sky, while Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla worked with science fiction writer Ted Chiang to create The Great Silence.In this fable,critically endangered Puerto Rican parrots living near the Arecibo Observatory witness humanity’s search for life beyond Earth. In this story, other intelligent forms of life, including the parrots that comprehend the secret “sounds” (vibrations) of the universe, are actually all around us.

“Floating Civilizations” turns to questions of humanity’s long-term survival in space. Can we adapt to the environments on different planets? Can we build new homes in places other than Earth? Many of the works in this section take a more sci-fi approach. Eyes in the Sky is a collage of found footage from the Dutch Film Museum and the European Space Agency, which envision and explore the cosmos as a slow floating balloon, rather than a piercing rocket. The Institute of Isolation presents an invented research and training institution. The protagonist spends time in an anechoic chamber researching the psychoacoustics of silence and conditions their body in a micro-gravity trainer, in an attempt to adapt to possible life in space. Moon Goose Colony, Lunar Migration Bird Facility (MGA) tells the story of a goose going to the moon based on Francis Godwin’s The Man in the Moon. From different perspectives, these works connect humanity’s perceptions, memories, dreams, tasks, and aspirations related to the universe. Florian Voggeneder’s artistic view on analogue missions connects these fictitious approaches with scientific aspirations in preparing for space travel. STONES by Quadrature and Olfactory Time Capsule for Earthly Memories by Ani Liu push these visions to their ultimate end, asking: When we depart from Earth, what can we leave behind so that other people can find us? On a one-way space flight, how do we retain memories of the Earth?

From “enveloping heaven theory” (huntianshuo) and hand-drawn star charts to modern technologies and cosmologies, we are constantly leaping toward the glittering, starry sky above us. It’s an instinct encoded in our genes. For thousands of years, nothing has been able to shoulder humanity’s imagination and hope quite like the night sky. We want to personally explore and discover our various connections with the cosmos.

References

Allan, Bentley B. Scientific Cosmology and International Orders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2007.

Sagan, Carl. Cosmos. New York: Random House, 2013.